I share an office with a few other writing teachers. One of my office mates, T., recently told me about her adventures in flower pressing, and she gave me some petals. Once curled and shaped, they are now paper thin and flat.

The pressed petals remind me of the bright, fallen, and wilted geranium petals on the floor of my room at Wellspring House, where I was in July for a week. The boards of the floor were painted gray, and when I walked in the room I saw a scatter of droplets — pink, with white edges — under the window. At first, without really thinking I thought they were painted fingernails. Then on the wide sill I noticed the clay pot, the green furred and scalloped leaves.

There are geranium pots on our front steps at home, and these too, like T’s petals, remind me of my solitary and spare room at Wellspring.

Petals, on steps after rain.

Thoughts of that room prompt memories of other loved rooms, especially two more: a dorm room, an office. What do they have in common? Why these three, and not so many others?

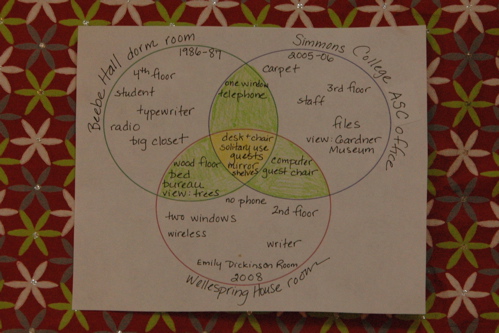

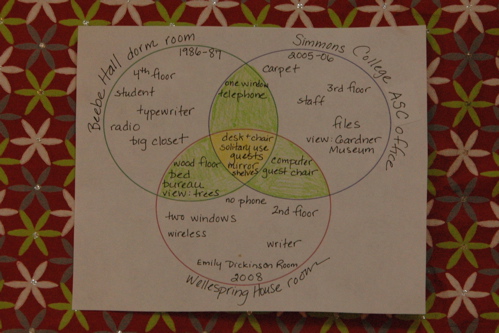

I make a diagram. (Later Lydia sees it and asks, incredulous, “You made a Venn diagram because you were bored?” I answer, “I made a Venn diagram because I was trying to figure something out.” She laughs kindly.)

Each room had its own wonderful qualities. The dorm room: a big closet and a typewriter. The office: a view into the greenhouse behind the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. The room at Wellspring was named after Emily Dickinson, and then there were the petals decorating the floor and catching my eye.

They shared some features too, and it must be these that cause me to consider them as a trio. All three had a desk & chair, shelves, and a mirror. They were intended for solo use, although I recall guests in each one.

"Three Rooms," by J. Kokernak, 2008.

I am ruminating over the importance of these concrete details and what they mean now. Each memory’s connection to my present life (and not my then student, staff, or retreater’s life) is what concerns me.

This exercise on the three rooms reminds me, too, of theme dreams (i.e., ones that recur). Mine are about secret rooms. In these dreams, I walk through a house I’ve lived in and find a door that I’ve never noticed before. I open it, and inside is a room that presents an opportunity to me (space, activity, style), and sometimes to the people I live with. Sometimes in one of my secret room dreams, I try to get another person’s attention: “Look, look at this! The room we’ve been wanting!” Sometimes in one of my secret room dreams, I close the door and keep its existence to myself.

About a dreamed secret room, Gillian Holloway, in The Complete Dream Book, claims that “This room has great possibilities… and represents a neglected potential in the dreamer’s life that the deeper mind is trying to reclaim” (155).

Are the three remembered rooms like secret dream rooms? There seems to be some bounty there.