No one is required to give credit to the source of the plants in a yard, although those sources are likely numerous: previous owner of the home, local nursery, hardware chain’s garden department, botanical society’s annual sale, mail order catalog, and other gardens.

The offspring of plants from other gardens are called “passalongs.” In the purest sense, passalong describes plants that are difficult to find and purchase through the usual sources and therefore must be propagated from a piece of an existing plant in an established garden.  (See Bender & Rushing’s Passalong Plants for lively essays on these heirlooms.) Some gardeners use the term, simply, to describe plants divided and shared among friends and neighbors.

(See Bender & Rushing’s Passalong Plants for lively essays on these heirlooms.) Some gardeners use the term, simply, to describe plants divided and shared among friends and neighbors.

In my yard, I have thriving raspberry canes, clematis vines, hydrangea bush, and ajuga spreads that started from cuttings originated in other gardens. All of these plants are standards I could find at a nursery, but they’re dearer to me because as I tend them I feel, in a way, as if I’m tending my connection to their givers.

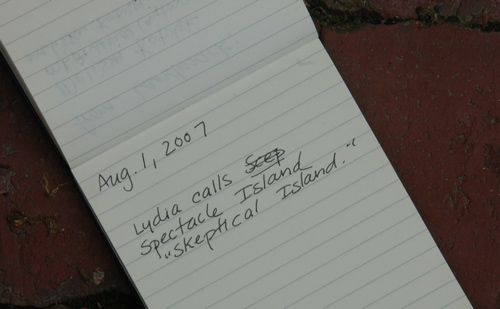

Last weekend, at my parents’ house, I deliberately harvested my own passalongs from their yard, 100 cuttings from a swath of pachysandra alongside their garage. Years ago I read, although I don’t recall where, that you can slice off the top few inches of a pachysandra stem, throw a whole bunch in a plastic bag,  add a cup of water, seal the bag, and then wait several days for the severed stems to root in this makeshift greenhouse. This project is motivated by a wish to transplant some growing thing from my parents’ yard to mine and also by a very blank space in an alley between my house and Bob & Mary’s fence.

add a cup of water, seal the bag, and then wait several days for the severed stems to root in this makeshift greenhouse. This project is motivated by a wish to transplant some growing thing from my parents’ yard to mine and also by a very blank space in an alley between my house and Bob & Mary’s fence.

The blank space, in fact, was once filled by my own lush pachysandra patch, bought in an immense quantity in flats from Home Depot, and then planted one compact dirt-and-root cube at a time in soil enriched with dried manure and then mulched over. They lived quite nicely in their shady, neglected conditions, and probably would have ad infinitum if not for the “rodent intervention,” i.e., rat barrier, recommended and then installed by an “urban wildlife expert,” i.e., exterminator. In one afternoon, he and his partner, with a friendly Golden Lab keeping them company, dug up the pachys to get at the foundation, to which they tacked a long, foot-wide roll of wire mesh. Only a few stems  struggled back from leftover bits the following spring.

struggled back from leftover bits the following spring.

Will this experiment work? Will the cuttings root in their garbage bag greenhouse? Will this decimated pachysandra patch rise up and fill in? In a few weeks, I’ll know.