I feared I had lost my attention span as a reader.

Over the winter, with so many work and family responsibilities, I maintained my daily commitment to reading (Jimmy calls it the “Jane Ten” — the 10 minutes I must read every night, no matter what, before I turn in — of which I’ve never missed a day) but only in fragments.

Here and there I read reviews in the New Yorker, articles in the New York Times or Onion online, magazine headlines at the grocery store check out, an essay or two from an anthology, and attachments sent my way by friends and colleagues: “Check this out.” I checked.

I wasn’t really reading, though. I was surfing the printed word. For me, real reading is a sustained, complete experience.

Honestly, I thought I had changed with the times. We multi-task. We browse. We lose interest. In April, I was worried it was over between me and books. They’re long! I don’t have the time! That was the inner dialogue of the new (fragmented, distracted) me.

The semester ended. Finally there was time to walk down the street to the branch library and wander its aisles and read jacket covers and first pages. I found the recent and umpteenth volume in my favorite series, the Inspector Banks mysteries by Peter Robinson. It was my transition back into whole books.

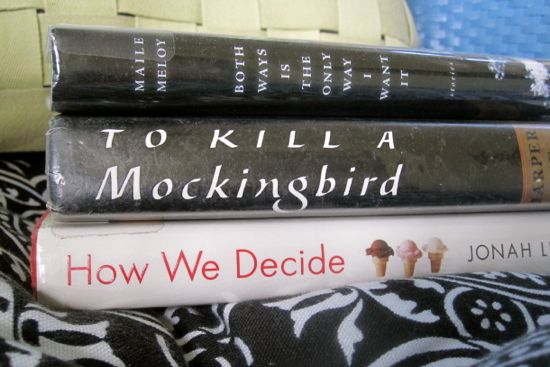

And the next three, one after the other, were Both Ways Is the Only Way I Want It (stories), by Maile Meloy; To Kill A Mockingbird, by Harper Lee (because I had never read it); and How We Decide, by Jonah Lehrer. Yes, yes, and yes.

I’m relieved that I am still a reader. That I wasn’t much of a reader (of longer works) during the academic year, however, tells me that having too much to do, in too many fragments, is an obstacle to sustained inquiry.

What other kinds of experience do our chopped-up days get in the way of?