Writing teachers, when they read drafts, have a hard time resisting the temptation of the ideal text. As we read student work, we may be simultaneously reading — or really, creating — an ideal text in our mind of what that draft could become. No doubt this ideal text is based on our knowledge of other texts we have read and perhaps even written ourselves.

Ideal texts may help us see our students’ work ambitiously, as though all writings hold great potential. Ideal texts may also prevent us from seeing the work for what it is and for what it wants to become, or for what the writer wants it to become. Brannon and Knoblauch (1982) describe how an awareness of ideal texts and the inexperience of students can lead a teacher in a way to “appropriate” her students’ work (158).

The kinds of texts we encounter at school can be more than essays or reports. Oral presentations are texts. Videos. Portfolios. A proposed experiment. In the project labs I am assigned to at MIT as a communications instructor, it seems to me that the engineering and science faculty read or consider their students’ independent design and research projects against some ideal that the faculty themselves conjure in the acts of reviewing and teaching.

This ideal-text creation is largely optimistic, and, at the beginning of the semester, we see only potential. The push is forward. Right around now, though, with only two weeks before the last day of classes, our ideal-text creation machine is seeming a little peaked, which can paradoxically lead to teacherly acts of will and desperation: extra writing conferences, more office hours, and lavish feedback.

There’s another tarnished ideal text we teachers are facing right now and that is this: our own teaching. Perhaps I should drop the communal “we” right here and admit that the tarnished ideal text that I am facing, at this late moment in the semester, is my own teaching. Way back in September, what I planned to accomplish and even be as a teacher was like a vision. And now I hold the reality of my teaching in my hands like a small pile of stones. Certainly, I have amassed something — I’m a better teacher now than I was 7 years ago when I started, and surely this has happened incrementally, including this semester — and yet the gains are modest-sized.

Oh, I’m not completely self-effacing. Not at all. As much as I’m seeing the shortfall in my work, I see too what I have achieved. In fact, nearing the end of the semester can be a weird time of reconciliation. Somehow, by making an account of what I didn’t accomplish, I force myself to look for what I have been doing: 4 classes and 60 students, and it looks like they’ll all reach the finish line intact and with a few flourishes.

I’m starting to reflect, too, on what my students have achieved, as I’m talking to them in meetings and conferences and as I think of them. I am reminded that they are not only the texts that they produce; they are very smart people to begin with who are growing as thinkers and doers, and teammates and teachers. In class, meetings, and peer reviews, I observe them teaching each other more and more. Often, I feel them teaching me.

—-

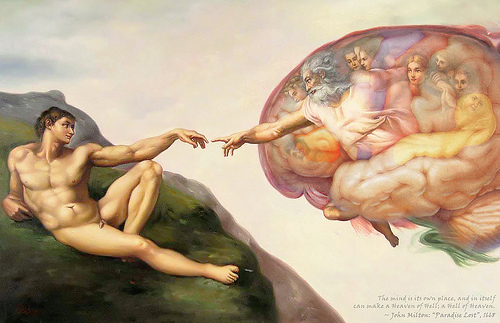

Image, “Brain of the Sistine Chapel,” by tj. blackwell on flickr.

Great post. It’s pushing me to count what I’m thankful for in my work instead of letting Thanksgiving fatigue get the best of me.

Explaining expectations to students is so tricky. I don’t mean to offer a template, but many students simply try to do what I “want.” And it’s difficult not to fall for the ideal that the expectations could lead a student to produce, even if I know better. If most of them interpret the expectations as I expected they would, I’m disappointed and want more. But it’s probably more than they could have accomplished before. And usually at least one student one does something surprising (in a good way), although a disproportionate amount of attention will go to the few students who just didn’t get it at all and wouldn’t have gotten it if [insert writing pedagogy deity of choice here] taught the course.

Thank you. And I’m glad you mention surprises. I had those on my mind, too, as I was wrapping up this post but didn’t want to introduce a new idea at the end. I have had some surprises from students in the last few days, and there are still a couple more weeks when there could be more.

I try to remind myself that sometimes we — and that includes me — learn from templates (if a template exists) and that we can’t really diverge from them until we’ve figured out a standard way to do something.

I want to have a longer conversation with you about this, but right at this moment I have to get back to reading drafts! Later…

Jane,

This is indeed a good post. I know just what you mean. It seems to me that I do exactly the same thing — work from a vision of what the student’s piece might become, which is my vision of course. I feel this is a pretty big piece of what I have to offer them. But it’s not as though I’m *right* about what their piece *should* become (even if I think I am) — I think what I’m offering them is that I have a positive vision of its becoming, with some concrete attributes so there is something they can try out as a revision. Still, the piece doesn’t become whatever my vision is, and that’s good. Like the first commenter, I’d probably be disappointed if it did. This is probably what leads me to work in an empirical way — see what the students do, then try to be led by that.

I know what you mean about the point of two weeks to go in a course. Not only is everyone worn down, but that’s about where I start to realize I have to let go of some of the vision I held for each student. It’s the beginning of letting go of them altogether. The work is what it is, and it’s their work. I mean, I keep trying to help them improve it, but I also start realizing we’re probably only going to go so far. In a sense I start abandoning them, and I justify it by remembering that if anything about this course worked for them, it’ll have to work without me in just a couple of weeks.