The car as text. (The rear end is not just for bumper stickers.)

Author: jelizabeth

The dead don’t change

The dead don’t change.

Whatever they were in life, they are now.

–Robert Sward (poet), 2006

Speak, Memory, about a dress

On the road from World’s End to the harbor, we drove through Hingham center slowly enough that I could look at store windows as we passed. In one, I saw a dress that turned my head. The image of it hovered in my imagination as we walked through the farmer’s market, bought homemade cider donuts, and sat on the strip of sand, ate donuts, and looked out at the boats and one swimmer.

I wanted the dress that I was remembering.

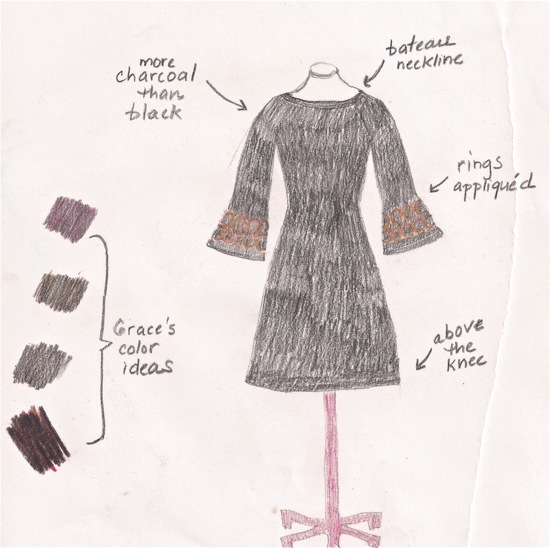

In my mind, I saw dark wool knit more charcoal than black, trumpet sleeves wrist length, and the only ornament a double row of appliquéd rings the color of coffee ice cream on the bell of each sleeve.

I told Grace and Jimmy about the dress and said I wanted to stop and look at it again on our way back to the highway.

It’s funny how memory works: when we got back to the store and I was standing on the sidewalk and taking pictures of the dress, I could see how my version of the dress was both like and unlike the original. Already, my imagination had refashioned the dress into what I wanted it to be. Continue reading

Tattered no more

Many readers or watchers of The English Patient (I preferred the novel) were swept away by the romantic story line: the Count and Katharine, their illicit liaisons, the plane crash, desert cave, fire. And I? In both the film and the book, I was drawn to the nurse’s story: Hana, her makeshift hospital, and her care of the burned and disfigured English patient.

Real love, in my view, is seldom epic. It’s steady and practical, and it accumulates in small gestures.

One of the to-do items on a long list of preparations and purchases for Eli’s move to college was mending. Months ago he left three pairs of jeans on the window seat in my room and asked me to make them wearable again. I don’t feel like mending during the school term — I’m too busy mending drafts, I guess — so I put off the task. Last week, a few days before my first child’s departure, I set up the sewing machine, looked at the pants with their three sets of problems, and sat down with scissors and sewing box.

One of the to-do items on a long list of preparations and purchases for Eli’s move to college was mending. Months ago he left three pairs of jeans on the window seat in my room and asked me to make them wearable again. I don’t feel like mending during the school term — I’m too busy mending drafts, I guess — so I put off the task. Last week, a few days before my first child’s departure, I set up the sewing machine, looked at the pants with their three sets of problems, and sat down with scissors and sewing box.

Only one pair was ripped on a seam line, an easy problem to solve, although a rivet through three layers of denim created an obstacle for my non-industrial machine. Solution: remove the rivet, using a hammer and small chisel, and sew along the existing seam lines. Done.

Two pairs weren’t ripped so much as tattered. Eli, through use, had worn the fabric down in the seat and around his wallet pocket. “Couldn’t I just buy you two new pairs of jeans?” I asked him. “I love these,” he said. “Couldn’t you just try to sew them?” Then he flattered me: “Mom, you can do it.”

Anticipating that more fabric would be needed, Eli had given me an unloved pair of denim shorts to cannibalize. I cut patches from these shorts and pinned them to the tattered places. I tacked them in place using a zigzag stitch.

Then I dialed the stitch setting on the machine back to the straight stitch, and I randomly and repeatedly sewed back and forth across the patches. This was true patching, building up a new fabric, in a way.

I kept my foot on the power pedal, periodically pressed the directional switch to reverse (the “back” of the back and forth stitching), and watched the stitches gather and blur into each other. I switched thread color, from gray to light blue for the denim ones and khaki to stone for the corduroys, to increase the blurring effect.

I thought about leaving my signature somehow, writing a word in stitches that would be like a secret message — one so secret only I would know about it — for the mended pants to carry around as Eli wore them. Mom, Jane, love all seemed too corny. (Plus, how twisted would that be, to write your own name in your son’s pants?) I considered hieroglyphs, which would fit invisibly into the random stitching, or tattoos or Japanese characters.

No symbolic language, in the end, made it into the mended pants. After I finished sewing, I snipped all the loose threads and admired my own work. We threw them into the wash, and Eli folded and packed them into his suitcase* for college. The pants and Eli live in Vermont now.

*Wait, there’s more! In trying to lift Eli’s overstuffed suitcase into the back of the car, I hurt my toe. Of course, I had to find a way to write about that. I called it “Toe Story” and posted it on my other blog. Link. There were sequels: “Toe Story 2” and “Toe Story 3.” Link 2 and Link 3.

The girl with silver hands

On Tuesday night, after a gap of five years, our friends the Zimmers came to dinner.

Ulrike and I met 17 years ago, in a manner that is not unlike the beginning of a romance. I was sitting near the window in a coffee shop in Brookline Village, looking out, and she was walking by, looking in. Our eyes met, and, although we were strangers, we smiled a greeting. The next day, or perhaps the day after that, we recognized each other at our children’s nursery school. Instantly, it seems now, Ulrike and I were friends.

We were neighbors during the time she, her husband Claus, and first daughter Pauline lived in Brookline. I look back on that as a golden time, although some of what we discussed during our countless moments together, alone or with Pauline and Eli, was rooted in the struggle to figure out who we were now that we had become mothers.

And, I dare say, if we had had more time together this week, we would have returned deeply to those mutual concerns: Who am I? What work am I most suited for? What do I want for myself? Where is that line between where others end and I begin? When the Zimmers moved back to Germany in early 1996, I lost a daily connection to a rare and intimate friendship. Yes, letters and email and infrequent visits can keep us in touch, but we are missing out on the incremental and ordinary comforts of being nearby. Shared life.

On Tuesday night, Ulrike brought us presents. To me she gave a pair of beautiful, silver leather gloves from a famous German glovemaker. “For the skater,” she said. I felt known by my friend, as though she had recognized the ‘me’ that I am, alone. Not the mother, not the teacher, not even the friend. A true gift.

Today I wore them for the first time. Little by little as I learn how to skate, I have been progressively marking my commitment to it in concrete ways: the purchase of fitted ice skates; the private lessons; the summer practice time; notebook; and gear bag. This is my first piece of costume.

Today I wore them for the first time. Little by little as I learn how to skate, I have been progressively marking my commitment to it in concrete ways: the purchase of fitted ice skates; the private lessons; the summer practice time; notebook; and gear bag. This is my first piece of costume.

I skated neither better nor worse today. In fact, one of the rink regulars, whom I recognized but don’t know, skated up to me and gave me some unsolicited “skater’s advice,” as he called it, which, he promised, “will give you more power.” (I found this to be extremely irritating, and I wish I had had the perfect comeback. Mad at him, I turned my back, but later tried what he suggested. I vow, though, to never thank him.)

The whole time I skated, I felt my gloves on my hands, and they seemed to be helping me steer into the future, when I will only skate better.

On our last afternoon together, Ulrike was brainstorming ways to get me and my family next to Munich for a visit. (Business trip? Frequent flyer miles? House swapping?) “We cannot let five years go by again,” she said.

“Yes,” I say. Our words make a promise to the future, when we will see each other again.

—–

—–

The title of this post is an homage to the Brothers Grimm’s tale, “The Girl with Silver Hands” or “The Girl without Hands.” The photographs were taken by Grace Guterman.

A feedback lexicon

Leave it to others to run marathons.

I, instead, participate in another endurance sport: the writing of miles and miles of comments on student writing.

In the past two weeks, in addition to having to submit the final report (with data) on a grant project I collaborated on, I wrote substantial comments on 40 essays and 28 research posters for two summer projects. There was so much to do in a short period of time that last Sunday morning I was sitting at my laptop at my dining room table at 7 a.m. to begin a day’s work.

My comments are typed, so I have a record of them, and for each project I copied and pasted them into one file to look at them for good language for future comments: Did I come up with a tactful yet straightforward way of saying, for example, “This has no evidence”?

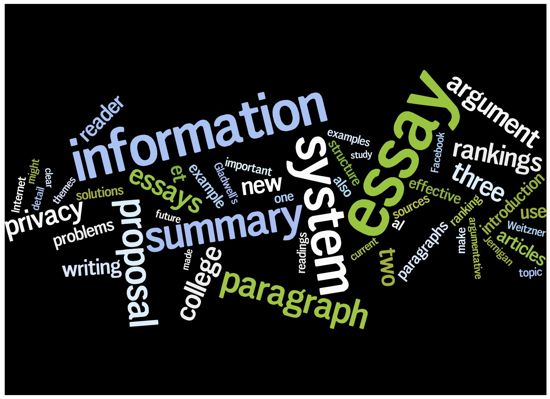

Although I continuously referred to the rubric, I had no way of knowing, however, if there was any consistency to my comments as I was doing them. So I turned to Wordle to see if there were any patterns, and I hoped that what Wordle revealed in its illustration of my feedback lexicon would have some relationship to my intentions. Before I created the word map, therefore, I wrote down a list of terms I thought/hoped I used more frequently.

You can see the Wordle of my top 50 words as the illustration at the top. Most of the words have to do with writing features or issues (e.g., paragraphs), although some of them have to do with the topics students were assigned to write on (one topic was information privacy and the other the college rankings system). I’m relieved to see that there is some relationship between my key words and what I recall of the rubric.

And there is also some relationship between the words I recall using most and the words I used most. Here’s the list of terms I wrote down before doing the Wordle, with some comments on their appearance in the graphic:

- information (appears first on my list and is prominent in the graphic)

- readings/sources (“articles,” “readings,” and “sources” appear in the graphic)

- summary (strong in the graphic, too)

- propose/proposal (ditto)

- illustrate (not in the graphic, although “example” is)

- some/more (not in the graphic)

- understanding (not in the graphic)

- synthesis (not in the graphic)

- detail (in the graphic, quite small)

- citation (not in the graphic)

So, one disappointment in my comments is that the word “synthesis” does not appear in the graphic of my top 50 words. One of the requirements of the summary prompt was that use of sources be synthesized. Ideally, I would have commented on whether or not a student did that in each essay. Perhaps I used synonyms (e.g., integrate or weave), but I may have missed a chance to emphasize this important terminology, which should become familiar to a college writer early on. Same for the word “citation” — I wish that it, or acknowledge or attribute or cite, appeared on the list of top 50. (It’s possible that source/readings/articles/use in some combination are how I addressed this in the comments, though, and all four of those appear in the graphic.)

And yet I do see some terms on the graphic that are really important in academic writing: argument, paragraph, structure, examples, reader, problems, topic, and even essay.

I did this as a reflective exercise. In future comment writing, I might try this midstream as a kind of quality control: am I hitting all the notes I want to hit? what could be dropped (my use of the tentative “might”)? what could be more emphasized (the word “idea”)?

Shaving the devil’s neck

The neck of my 18-year-old son was bent over the bathroom sink, and I took this as a good moment to bring up the subject of recreational drug use. Eli was heading to Gathering of the Vibes, and he had spent the morning packing the car and communicating with the two buddies he was traveling with. Time ran out, and, instead of going to the barber shop, he enlisted me to cut his hair and shave his neck.

“Eli, I know there can be a lot of fun and debauchery at these music festivals.”

“Eli, I know there can be a lot of fun and debauchery at these music festivals.”

Silence from the young man.

I pressed on. “On Sunday I read an article in the newspaper about this new drug – “

Eli interrupted me. “Yeah I read that. Bath salts.”

“Right, bath salts. Anyway, so a lot of times at these big public festivals, people are having a good time – and I totally get that – and sometimes doing impulsive things. Like saying yes when someone offers them a new drug. They think, oh, what the heck.”

Eli was shirtless, and my hand was on his naked shoulder. He sat on a desk chair I had pulled from a bedroom into the bathroom and faced the sink, not me. “Mom, everyone knows you should never buy anything from someone you don’t know.”

“I’m not sure you are getting my point. Eli, people are getting pretty fucked up from this drug. The damage lasts for months.” [Note: This is the first time ever I addressed Eli directly with the F-word. It was the best word in the situation.]

“Mom, I am not stupid.”

“I don’t think you are. But I do think people let down their guard when they’re having a good time and – “

“Mom, I am not interested in bath salts.”

“Well, I just wanted to bring this up so you could think about it ahead of time. I don’t want you to make a foolish decision and end up in the emergency room.”

The wet shaving with a razor hadn’t been going so well, so I wiped the white Noxema foam off his neck and tried the electric shaver. Not as close a shave, but an easier go for me.

“Mom, did you ever think that article is exactly in line with the anti-marijuana propaganda of the thirties?”

“What?” I asked him. I felt disoriented, and I wondered if I had spaced out during some point of our conversation and lost the logic trail.

“So that article in the New York Times could be propaganda, attempting to frighten people just like how propaganda in the 1930s tried to get people to fear marijuana. Notice how the reporter didn’t include any information from people who were not hurt by using it.”

Whoa. He changed the terms of the argument. I never know what to do when this happens – when a smart and quick-witted person throws me a conversational curveball. Often, I end up mute, an argument loser.

“Eli!” I was scrambling. All I could think of was his name and my tone of voice: serious, plaintive.

“Hey, Mom. Be cool. I’m just playing devil’s advocate with you. Can’t you tell?”

His neck was as smooth as I could get it with my amateur hands and tools. I wanted to abort the conversation right there. There was no way I could win, persuade him, get him to the point where he would say, Mom, thank you so much for bringing this to my attention. Obviously, you care a lot about me and want me to be safe. I am going to heed your words. If only. Continue reading

Little garage on the prairie

Last summer, after I dug up all the potatoes in my first patch ever, I cooked some and set some aside. I also hung brown grocery bags of potatoes by bungee cords from the overhead door track in the garage. I didn’t want to hang them in the cellar, fearing a rodent attack. So, a ‘root garage’ would have to do.

Last summer, after I dug up all the potatoes in my first patch ever, I cooked some and set some aside. I also hung brown grocery bags of potatoes by bungee cords from the overhead door track in the garage. I didn’t want to hang them in the cellar, fearing a rodent attack. So, a ‘root garage’ would have to do.

Over the fall and winter, we ate some potatoes. The garage is unheated, and yet they didn’t freeze. Feeling very much like Caroline Ingalls, a hero of mine, I left quite a few in the bags uneaten, as seeds for a future patch.

Well, this spring I did not do potatoes. I wanted a break from caring for so many living things to tend to other interesting challenges (writing, skating) as well as to children and students, who cannot wait. I suppose Caroline Ingalls, more legitimately concerned with survival than I am, would never have taken a break from kitchen gardening — it would have short-changed the family’s diet profoundly.

Recently I commenced the annual summer ritual: the garage clean-out. (Why doesn’t the garage stay cleaned out? We haven’t accumulated any new garage stuff.) The bags hung there, still dry, and no rotting potato juice stained the bottoms.

It had been months since I looked in. I imagined a bag full of potato raisins: dried, shrunken, and tough nuggets. What I found: intact purple seed potatoes, sprouted, reaching their arms up to me, begging to be planted.

Did I plant them? If I were Caroline Ingalls, I would have.

But I’m not her, and I didn’t. Off to the compost they went. Their bountiful energy will go into some other growing thing.

Skating story, told and retold

This week, for the first time in a year, I saw my friend Lisette, who is like me a teacher and unlike me a former college athlete. Around the time I started teaching college writing (eight years ago), she said to me, “It’s good to do one new thing every semester that gets you out of your comfort zone.” This was an idea she had picked up, I think, from her college volleyball coach.

On Tuesday afternoon at the playground, I told Lisette and her oldest son Griffin about a little skating accident I had recently, and how the coach made me get back on the ice as soon as I could stand again.

It’s good to have friends and coaches that prod you to take risks, especially when you are not naturally inclined to some kinds of them.

And, of course, I had to write about my fall. Find the story, published here.

Wrecked by belief: the true story of a verdict

I have read some reporting and commentary on the Casey Anthony trial, especially in the last few days. Something went wrong there, and I too believe that the little girl died by neglect, maltreatment, or malicious intent. The mother is surely guilty of some serious, serious wrong. Although the stories constructed by the prosecution and the defense seem flimsy, still my sense of how humans behave tells me that the mother harmed her daughter enough that she died, and then with her family’s help she obliterated the physical evidence.

I have read some reporting and commentary on the Casey Anthony trial, especially in the last few days. Something went wrong there, and I too believe that the little girl died by neglect, maltreatment, or malicious intent. The mother is surely guilty of some serious, serious wrong. Although the stories constructed by the prosecution and the defense seem flimsy, still my sense of how humans behave tells me that the mother harmed her daughter enough that she died, and then with her family’s help she obliterated the physical evidence.

And yet I am not appalled or surprised by the jury’s verdict of “not guilty.” The prosecution’s case was built on circumstantial evidence. The job of a jury is to judge the facts of the case as they have been presented. Were there enough facts?

In 1998, I served as a juror on a criminal trial in Massachusetts. A teenage girl had accused her stepfather of sexually assaulting her, and the Commonwealth of Massachusetts prosecuted him for the charges. Along with my fellow jurors, we found the girl, whose first name was also Jane, to be a totally credible witness, and we believed that she had been harmed by Dennis, her stepfather, and also by her mother, Wendy, who took the stand in support of her husband and undermined her daughter’s testimony.

The case built by the Commonwealth, however, became an exercise in He Said/She Said. The Quincy Police had gathered no physical evidence, no material witness.

In 2003, five years after the trial, I wrote a short account of my experience for a graduate school class on pedagogy at Simmons College. Each of us had to write in response to a prompt that one of our classmates had designed as something s/he would assign to high school or college students in a writing class. The prompt I addressed asked me to reflect on Robert Frost’s poem, “The Road Not Taken,” and describe an experience in my life in which I had had to make a difficult choice. I didn’t pretend to be a high school writer; I wrote the essay [read it here] from my age and experience. Continue reading

_____

_____