The 2010 vernal equinox is not until March 20 at midnight, but I’m quite comfortable with the Kendall Flower Shop in Cambridge, MA having declared it BEGUN!

Author: jelizabeth

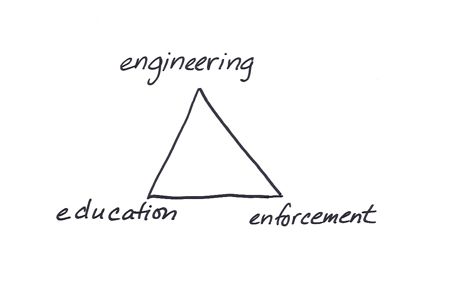

Three E’s: a paradigm

Years ago, when I was freelancing as a development researcher and writer, I helped the director of a new institute on children’s health prepare for a speech. I did the research that framed her remarks, which she wrote and ultimately presented to an advisory board. This was before the proliferation of Web-available information (in fact, Lydia was 8 weeks old at the time — 14 years ago!), and I conducted the research like a gumshoe, going stealthily from library to library, consulting periodical indexes, photocopying articles, and interviewing researchers.

At the Educational Development Center in Newton, I spoke at length to a library associate who first interviewed me, as a way of getting a bead on my questions and assignment. She asked me if I was familiar with the “Three E’s,” a neat way to think about public health problems, and she drew a simple diagram on the chalkboard in her office.

She explained that there are three kinds of approaches to addressing and attempting to solve entrenched problems, like teen pregnancy or gun violence: engineering, enforcement, and education. “Say you want to address rising teen pregnancy. An education approach would be to design a school-based curriculum at prevention. You might try to meaningfully inform teenagers about the responsibilities of parenting and offer them pragmatic advice about contraception. An enforcement approach would be to segregate pregnant teens from the main school program — this might be a disincentive to nonpregnant teens. The engineering approach would be the offering of Norplant, free of charge and through a school’s health clinic, to sexually active girls.” She added, “Whenever you can come up with an engineering solution to a health problem, it’s easier and usually more effective because it minimizes the human behavior aspects that enforcement and especially education rely on. Education is the hardest way to affect change.” Continue reading

Resonance, wonder, and toys

In his essay “Resonance and Wonder,” Stephen Greenblatt writes about two powers permeating the works of art in museums:

By resonance I mean the power of the displayed object to reach out beyond it formal boundaries to a larger world, to evoke in the viewer the complex, dynamic cultural forces from which it has emerged and for which it make be taken by a viewer to stand. By wonder I mean the power of the displayed object to stop the viewer in his or her tracks, to convey an arresting sense of uniqueness, to evoke an exalted attention.

Read his essay (a .pdf is here), and your experience of artifacts in museums may be forever enriched as mine have. In this post, I translate his ideas and use them to consider toys, Jane Eyre, The Matrix, and other things that stand in for objects.

When you first encounter an object — especially one you instantly are wowed by — you stand in wonder. There’s something really personal about that experience. You feel delight, surprise, enchantment. It’s an oh my god! moment. Greenblatt says that museums like MoMA amplify wonder with tactics they use to display objects, with boutique lighting, for example, which throws a pool of light around objects in a dimmed room, in the same way that jewelry stores and designer clothing shops do. Lighting isolates an object and hold it up for display. That isolation is important: it intensifies your wonder. It’s immediate, with no past or future; it’s love at first sight. Continue reading

– Last skating day

We missed the last skate, Grace and I.

We missed the last skate, Grace and I.

By last skate, I mean that we missed the last day of the season at the outdoor rink at Larz Anderson Park.

On Sunday night, the last skating day, the one we missed, I sat downstairs in the living room, writing comments on report drafts. Around 10 o’clock, I heard the sound of weeping. A child. I went upstairs and located Grace, who had woken up. She cried softly, with a kind of tinkling music that probes your thoracic cavity with its fingertips.

“What’s wrong? What’s wrong?” I murmured.

She didn’t move or thrash. With her lips a little mashed by the pillow she said, “I just feel sad. I don’t know.”

“Sad about something?” I asked.

“Just sad.” She paused; she wept. I could see the sparkle of her opened eyes even though the room was dark, because the light was on in the hallway and her wet corneas caught it. “We missed the last skating day today.”

“I know. I’ve been thinking about that. We should have made ourselves go.”

Grace sighed. “It’s that, but it’s not just that.”

I know that, too. Sometimes a person just feels sad, and a concrete event amplifies the sadness, but it doesn’t entirely explain it.

We adults often believe that we own those deep emotional cavities that inexplicably open up inside a person from time and time. While they last and remain open, nothing will fill them. One thing that being a parent has taught me is that children experience the unfillable eternity, too. Lydia, at six, sobbing, retorted when I asked her what was wrong: “If I knew why I was crying, I wouldn’t be crying!” Eli, at ten, soberly informed me: “Mom, if you think that kids are carefree, you don’t know.”

What is the comfort when there is nothing to say? On Sunday night, the last skating day, I climbed into bed with Grace; I was tired anyway. She flung her arm over me. We slept together for an hour, animal to animal. Eventually I got up, looked again at her, and shuffled to my own bed.

—–

Photograph of the rink at Larz Anderson taken by Grace Guterman at 4:30pm on February 18, 2010, ten days before the last skating day.

– I am my own handyman.

The appliance store delivered the dishwasher; the plumber hooked up the water in and water out; and the electrician powered it. Yet, there it sat, half in and half out of its cubby, waiting for someone to ease it into place, adjust the feet and level the orientation, screw the brackets to the countertop, and install the plastic guard and metal toe kick.

The appliance store delivered the dishwasher; the plumber hooked up the water in and water out; and the electrician powered it. Yet, there it sat, half in and half out of its cubby, waiting for someone to ease it into place, adjust the feet and level the orientation, screw the brackets to the countertop, and install the plastic guard and metal toe kick.

Well, today that someone was me. How frustrating. How ultimately satisfying!

During all that time on the floor, I meditated again on the ratio of time spent mending things to time spent making things. Is this where my creative energy gets spent? Hmmm. I felt sorry for myself and all my quotidian concerns for a few moments and then answered my own question: “Not entirely.” This task is simply more finite and results observable than writing or research or teaching. And immediately useful! Finally, a working dishwasher.

—–

P.S. The title of the post is an homage to a wonderful one-actor play, I Am My Own Wife, performed by Philip Leal, which I saw with James Black in Houston in 2007. If I recall, we were the best audience members that night: engrossed, moved. The Houston crowd seemed polite, yet perplexed.

– Grades beep, rattle, and hum.

But grades don’t speak.

It’s report card week in Brookline, and as usual we got a heads-up e-mail from the high school headmaster, prodding us to ask our sons and daughters to hand over their quarterly assessment. “The report card is an important school communication,” he concluded.

One thing every parent of a high schooler knows is how little communication there is between home and school, especially compared to the mountain of notices, bulletins, and newsletters that come our way during the K – 8 years, not to mention the PTO breakfasts and principal’s coffees and “special” events. (For the record: I do like parent/teacher conferences.) Eli is a junior in high school, and I met his teachers once at an open house event. Yes, I had a nice and helpful conversation with a few of them. However, that and a few visits Jimmy made to similar open houses constitute the extent of home/school communication in the last three years. I’m generally okay with that, but I am not okay with grades standing in for communication.

Grades might be aggregated data, and they might even be signals, but, because they lack (a) teachers’ interpretation and (b) opportunity for direct feedback, they cannot be communication. Continue reading

– Draw a picture. Make a sandwich. Teach writing.

During a scheduled hour to discuss their upcoming proposal drafts, I asked a group of 10 chemical engineering students to explain to each other their research projects, the rationale, the experimental design, and prior research. They talked productively for a half-hour and listened to each other with curiosity and asked relevant questions. All good. Certainly, we could have filled the rest of the hour with more talk.

I looked at the classroom’s two white boards and one easel pad and clutch of dry erase markers and Sharpies. I invited them, instead, to draw.

In small groups, they drew branching diagrams of their proposed experiments and explained their plans — and, even more importantly, gaps in their plans — to their peers. I walked around. They asked questions about how they might frame their experimental design in their drafts.

My friend and colleague Lisa had the classroom reserved after me, and she came in five minutes before we finished. Later, on the way to the copy machine, I saw Lisa’s students (in a different section of the same class) sprawled on the floor with big pieces of white paper and clustered around the white boards, drawing and gesturing with hands and markers. Continue reading

– It’s here! It’s here!

The table of contents is here!

The table of contents is here!

Those are the words that rung through my mind’s ear as I opened issue number nine of P•M•S poemmemoirstory and saw my name in the table of contents next to “Little Creatures,” an essay on lice and love.

I was thinking of the early scene in the Steve Martin movie, The Jerk, in which the phone book arrives and Navin Johnson cavorts in joy: “The new phonebook is here! The new phonebook is here!” (Relive it at 1:24 in this trailer.) His name, in print! My name, in print!

Alas, though, it’s only a name. If you want to read my essay on experiences delousing my three children, leave me a comment with your e-mail address and a PDF will be yours.

And if you came here looking for the BEST LICE TREATMENT or a LICE REMOVAL MACHINE, which are among the top search strings that lead people to my blog, then let me give you the information you came for: Continue reading

– Lover of carrots

In my house, I have frequently been called “Lover of Carrots,” or “LoC” for short. Honestly.

And I do love carrots. I eat them raw every day. (My limit is a half-bag of those baby ones.) They taste good; they’re a habit; and — I also realized on Monday, when I felt overwhelmed by every work, house, and family task on my list — the chewing is a release of tension. Mouth exercise?

Perhaps it is not so illogical, then, that I thoroughly loved my raw food/vegan meal at Grezzo Restaurant in Boston, even though I am not currently a vegetarian. And that I had such wonderful company in my friend, and movie partner-in-crime, Betsy Boyle, helped.

– Fragile, dear, and broken

Sometimes, in one of my little fantasy conversations, I imagine saying to the phantom I’m talking to, “I am not a person who breaks things.” I imagine saying this not as a boast but as a deeply held commitment, a promise to myself: I will take care, I will not break. And when I say “things,” I mean everything that can be broken, like dishes, and promises and hearts, too.

But, of course, I am occasionally a clumsy animal, and I break things. Two hours ago, for example, I broke two snow globes. This made my daughter cry.

We were on our way to school. Lydia was riding shotgun, and Grace was in the back seat with her backpack, music bag, and a mysterious bundle wrapped in a fleece baby blanket. After I stopped the car in the drop-off line of other cars in front of the school, I reached into the back seat and tried to push this swaddled bundle closer to Grace, who was outside the car now and trying to figure out how to carry everything.

The bundle slipped off the seat onto the floor. I heard a little grind. Grace burst into tears. “You broke them, you broke them, you broke them!” Continue reading