There’s a kind of making that’s really just manufacturing. There are no choices or problems to confront. No risk. No surprise.

I’m manufacturing a scarf as I sit on the sidelines and wait for Grace to finish her swim practice. Oh, early on I had to make one or two decisions — which of my surplus yarns should I use? how many stitches do I cast on? — but now all I have to do is pick up the needles and start moving my hands to operate the tools in a way I’ve done a thousand times before. As Lydia remarked a few weeks ago about this kind of knitting, it is calming, and it is productive. Row after row after row, the inches add up. I could almost knit this in my sleep. I want the scarf, which is intended for me, yet I feel no urgency about it.

I’m manufacturing a scarf as I sit on the sidelines and wait for Grace to finish her swim practice. Oh, early on I had to make one or two decisions — which of my surplus yarns should I use? how many stitches do I cast on? — but now all I have to do is pick up the needles and start moving my hands to operate the tools in a way I’ve done a thousand times before. As Lydia remarked a few weeks ago about this kind of knitting, it is calming, and it is productive. Row after row after row, the inches add up. I could almost knit this in my sleep. I want the scarf, which is intended for me, yet I feel no urgency about it.

On Monday afternoon, Grace interrupted her swimming of laps, hauled herself out of the pool, and walked over to where I was perched, knitting and waiting for her. Practice was only half done. She looked spent.

“I’m tired. I don’t want to keep swimming today,” she moaned as she leaned against my leg. A conversation determined that her complaint was nothing diagnosable.

“It’s a tough practice,” I replied. “They’re not always fun.” I tried, as I always do when her confidence wavers, to be an external ballast: “You’re halfway there. You look strong.” Inside, I asked myself, Why not just go home? She’s only seven.

“But, Mom!”

With my hand resting lightly on her wet back, I murmured with firmness, “Grace, I know you can do it. Plus, we’re here.” At an education conference in the fall, I learned that children become self-reliant in their interactions with trusted others. It’s our job to coax them, paradoxically, to become more independent. Is this what that speaker meant? I wondered.

Unhappily, she walked back to her lane and slipped into the water. She looked to the coach for direction, and then she bent her knees, pressed her feet against the wall of the pool underwater, and pushed off. Stroke after stroke, Grace swam 25 meters, then 50, 75, and finally 100.

I looked down at the knitting in my lap and tried to compare my rows to hers. What’s different?

When I started teaching, my friend Lisette, a (former) serious college athlete who also became a teacher, asked me, “What are you going to do this semester to get out of your comfort zone?”

“Huh?” I responded.

“What are you going to do that’s hard for you, that you’re not sure you can do?” she elaborated.

I took her question seriously and thought about it for many days as I was planning the semester, and I built into my syllabus challenges not just for the students, but for me. With a silent nod across the miles to Lisette, I do that every semester.

When I do this kind of mindless knitting, however, there’s no risk for me and nothing of value at stake. Like eating ice cream, it’s soothing and filling in a pleasurable way. We all need those kinds of activities in our lives.

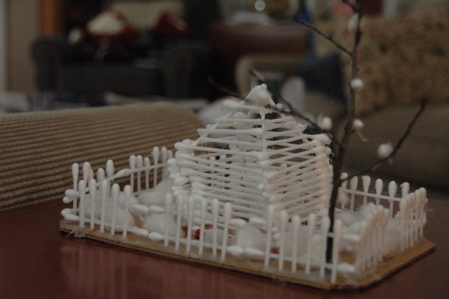

Grace’s rows in the pool, however, are different. She’s not always sure she’s up to it or that she can finish what she has signed on to do. There are tears sometimes, cold water, and nakedness in the locker room. There have been no measurable victories so far, although Grace keeps hoping for them, and hence no ribbons on a loop of thread to hang from her neck. And still, she must practice, practice, practice.

—-

Picture of scarf in hand by Eli. Picture of Grace by Jimmy.