I like talking to Leslie Sills, my daughter Grace’s art teacher, about process. She’s a sculptor and a writer, so inevitably we get to how making objects and making prose are alike, and unlike.

Once, in a discussion on finding time to do self-generated work, amidst teaching and other commitments, Leslie said, “Before coffee.”

“What?”

She elaborated: “I heard Katherine Patterson speak at the Brookline Library about her work. She said, “Write before coffee.”” Leslie has tried, and keeps returning to, this simple advice.

Intrigued, I tried, too. Many times in the last fews months I’ve gotten up about an hour before I normally would (time varies depending on weekday or weekend) and done some writing while I waited for the coffee to drip.

Here’s a long hand-written piece from early Sunday, October 28, presented to you as is:

So, then a hundred, then 50 more black birds, so black there was a bluish oily tinge to tail and head feathers swooped and circled into our backyard this morning, into Isaac’s, into Gail’s, and pecked for a few minutes in the grass. All the while, they were cackling together almost screaming. But not crows, not big enough to be crows. They must see well, to be able to see between grass blades the insects they peck at. They look purposeful: taking steps, peering down as if seeking, zeroing in, pecking.

When they first arrived, I saw them (I was looking out kitchen window) swoop in an arc from beyond Isaac’s house, in the air around his garage, some made stops in our Norway maple that’s on the property line, before hopping as solid as a stone or fleet as a bullet down onto our grass.

Bird squad. Bird squadron. Bird squads.

As if sensing a signal, the ones scouting the east end of our backyard lifted off and circled away. Hastily. As if being pulled by threads or by a signal that they senses second after, others took off a flew, too. In the crowd, there was a kind of order, even though I felt a kind of compressed hysteria in watching them.

Why did they arrive so swiftly, and from where? Were they hopping from yard to yard, satisfied to get one or two bugs per bird in each yard? Incessant moving, incessant feeding to fuel the movement, a cycle that cannot stop.

This must happen every fall and around this time. I remember in the fall of 2001 — only six years ago? — being home with Eli, and noticing the same pattern with the black birds. They swooped in, blanketed the front lawn, chattering and hunting, and then swooping away. It was ominous, marring, on a beautiful October afternoon. Eli said, “The birds know something. Because they’re in the air, they know what’s coming before we do.”

The terrorist attacks of 9-11 were on all our minds. Eli, only nine years, imagined the birds, like planes, in the air, sensing a familiar pattern (planes fly up there, “we” (birds) fly down here) altered, and knowing that something had changed and was changing, yet not being able to predict what.

And when it happened? Was it another fire for them — treetops burning, cracking, popping and falling — acre after acre — or was their familiarity with buildings and glass enough to tell them that this event was remarkable, something that doesn’t happen.

I couldn’t have written this at night, when there often is more free time to write, because the birds would not have presented themselves to me.

I doubt I could have written this before coffee, because the having of coffee makes me sharper, more thoughtful, deliberate. With coffee, would my mind have wandered to where it ended up?

—–

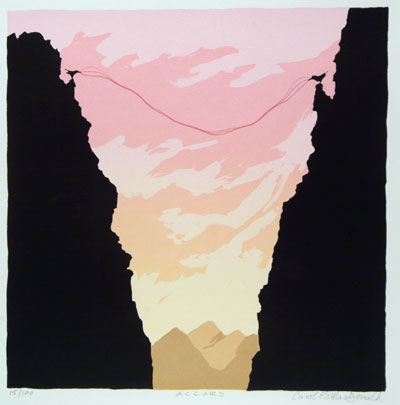

The image is from Grillboy’s Coffee Cup Project.