At least twice a week, I walk down the long hallway that is glassed on one side with giant windows that look out on the courtyard outside Hayden Library. I look, and I imagine sitting out at one of the tables and reading in the roofless room, enclosed on four sides and open to the sky. Sheltered/exposed. I look, but I don’t go through the door. And no one else seems to. We’re busy.

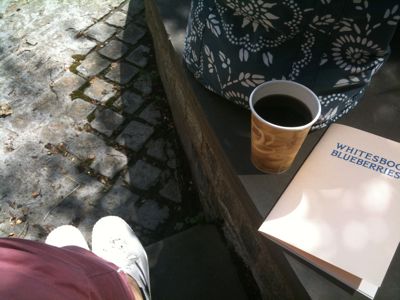

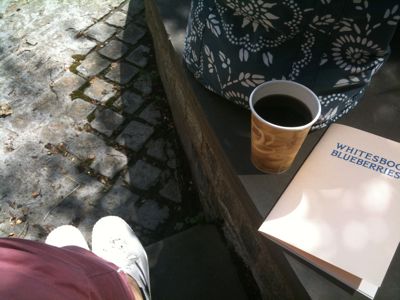

Finally, though, it’s a beautiful day, and I have an errand taking me to Hayden. Through Google Scholar I have found citations to three published articles relevant to my Elizabeth White project. I get coffee at the Clover truck. I head to the library and go through the door. Others have the same idea: there are two young women, with an open laptop, sitting at one table and talking, and there is another young woman at a smaller table, reading. I choose the steps, sit half in sun and half in shade, read a reprint of a pamphlet written by White, and drink the coffee. Already I am happy, like a bee among daisies.

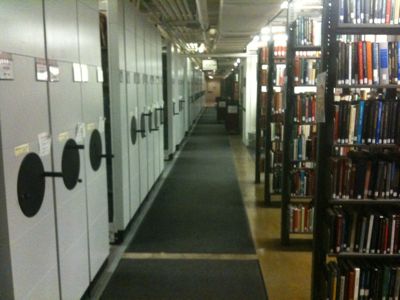

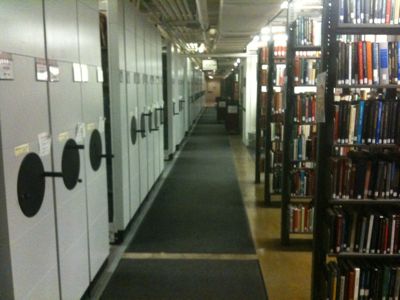

Coffee done, pamphlet read, I head down to the library basement, where the old bound journals cohabitate on those movable shelves. Down there I whiff the minerals of concrete and dust. The air seems to hum, but only because it’s so quiet, and I know that fluorescent lights are supposed to hum. The semester is over; I am alone.

I find the call number for the citations in National Geographic Magazine. Frederick Coville, the USDA botanist to whom Elizabeth White offered her family farm, Whitesbog, as an experimental agricultural station in the 1910s, published three articles in that decade that will help me with my project. Two are on blueberries: one published before White discovered Coville, and one after White and Coville bred a cultivated blueberry that could be farmed. Another article is on the first World War and the U.S. government’s concerns with the food supply in Europe.

Old books have a sour smell, not unlike the tang of expired milk or the acid of bile. When I was a girl and I would open a book with this particular smell in the library and breathe it in, I would consider it mildly vomit-y. I love this smell, and as I open each heavy book I drink it.

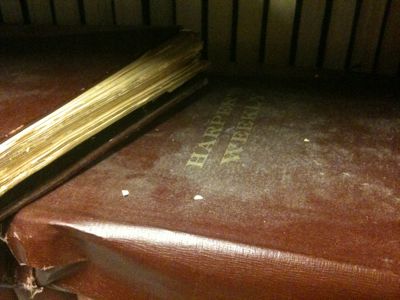

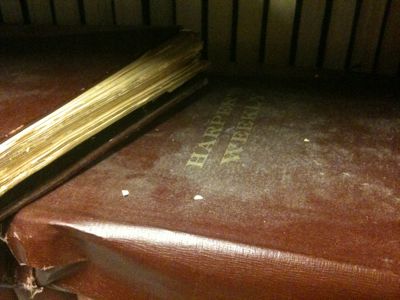

Facing the National Geos are a stack of skinny newspapers. I slide one off the top; it’s Harper’s from 1869. Amazing, I think, that this treasure is out on the shelf and I am trusted to put my human hand on it. It flakes along the fold when I open it wide. Carefully, as though it’s a sheet of glass, I close and arrange it back into place.

My friend Rosemary, doing her own research this summer, offhandedly described her surroundings as “musty old archives,” and reported that our mutual friend, Susan, herself an archivist, first took umbrage at the characterization and then softened: “Perhaps we [archivists] should embrace it.”

Ah, friends, yes. For those of us whose pulse quickens as our steps shuffle down to the library basement, hands open leather-covered and cool pages, eyes delight in the accumulated dust, and noses inhale the sour cloud of old ink while eardrums vibrate with the hum of what is surely our own heart: embrace it all.

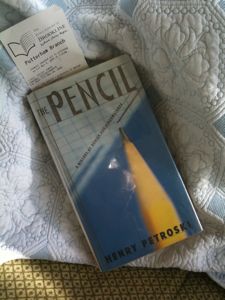

For some reason, Grace, Jimmy, and I were talking about single-noun-subject books. What concrete thing interests you enough that you would read or write an entire book about it?

For some reason, Grace, Jimmy, and I were talking about single-noun-subject books. What concrete thing interests you enough that you would read or write an entire book about it?