Years ago, when I was freelancing as a development researcher and writer, I helped the director of a new institute on children’s health prepare for a speech. I did the research that framed her remarks, which she wrote and ultimately presented to an advisory board. This was before the proliferation of Web-available information (in fact, Lydia was 8 weeks old at the time — 14 years ago!), and I conducted the research like a gumshoe, going stealthily from library to library, consulting periodical indexes, photocopying articles, and interviewing researchers.

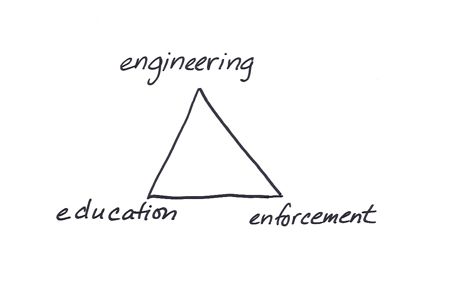

At the Educational Development Center in Newton, I spoke at length to a library associate who first interviewed me, as a way of getting a bead on my questions and assignment. She asked me if I was familiar with the “Three E’s,” a neat way to think about public health problems, and she drew a simple diagram on the chalkboard in her office.

She explained that there are three kinds of approaches to addressing and attempting to solve entrenched problems, like teen pregnancy or gun violence: engineering, enforcement, and education. “Say you want to address rising teen pregnancy. An education approach would be to design a school-based curriculum at prevention. You might try to meaningfully inform teenagers about the responsibilities of parenting and offer them pragmatic advice about contraception. An enforcement approach would be to segregate pregnant teens from the main school program — this might be a disincentive to nonpregnant teens. The engineering approach would be the offering of Norplant, free of charge and through a school’s health clinic, to sexually active girls.” She added, “Whenever you can come up with an engineering solution to a health problem, it’s easier and usually more effective because it minimizes the human behavior aspects that enforcement and especially education rely on. Education is the hardest way to affect change.” Continue reading