Items to keep in your school bag:

Not by nature a maker of fun, I do like to have fun, and I believe that others need it, too. Do you notice, for example, in a classroom, if the teacher is not providing any chuckles, a student in class will start performing that function? Intuitively, we all know, even if we resist the knowledge, that the Class Clown is essential. Just as every group could use a leader or two, every group could use a fun-maker.

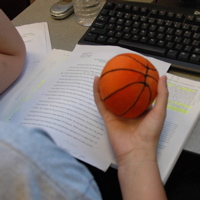

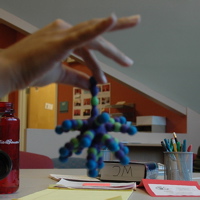

Even a serious teacher like me can design some fun. Props help. A few weeks ago, seeing that my September and October calendars were filled with appointments for visiting classrooms on campus and giving students my brisk “Come to the Writing Center” speech, I bought five toys. Diversely, they squish, boing, and bounce.

I bring them into the room and put them on the desk.  I introduce myself in 15 words or less, and then I ask the students to think for 30 seconds on this question: “What makes writing so hard?” I add: “Every answer is the right answer.” I wait. And then I hold up the first ball and I give my brief instructions: “I’ll throw this to one of you. When you catch it, say your first name, and then tell us what you find so hard about writing.” I toss, a student catches, and the ball makes a surprising, mechanical “boing” sound. He laughs. The group laughs. The catcher answers: “I’m Paul. And getting my ideas down is hard for me.” Yes, I say, that’s challenging, for all writers in fact.

I introduce myself in 15 words or less, and then I ask the students to think for 30 seconds on this question: “What makes writing so hard?” I add: “Every answer is the right answer.” I wait. And then I hold up the first ball and I give my brief instructions: “I’ll throw this to one of you. When you catch it, say your first name, and then tell us what you find so hard about writing.” I toss, a student catches, and the ball makes a surprising, mechanical “boing” sound. He laughs. The group laughs. The catcher answers: “I’m Paul. And getting my ideas down is hard for me.” Yes, I say, that’s challenging, for all writers in fact.

I give another stage direction: “Paul, throw that ball to one of your classmates. It’s someone else’s turn to tell us her first name and what’s hard about writing.” The next person answers.  After that I introduce a new toy, and then another — they’re getting the hang of it now — and learn a few more things about what makes writing hard for students: “grammar,” “finding the right word,” “thesis” (over and over), “getting the length right,” and “starting.” Within a few minutes, all five toys are in play, and the students seem to have figured out the drill, and they’re looking at each other, waiting for a turn, aiming if they’re throwing, and talking to me and each other. The game, furthermore, is giving me material; I’m not a lecturer, and I get most of my energy from the questions and thoughts that students bring to or make in class. In this case, their responses give me an entrée to a conversation about how 1:1 tutorials in a writing center support students at all stages of the writing process and for any writing challenge.

After that I introduce a new toy, and then another — they’re getting the hang of it now — and learn a few more things about what makes writing hard for students: “grammar,” “finding the right word,” “thesis” (over and over), “getting the length right,” and “starting.” Within a few minutes, all five toys are in play, and the students seem to have figured out the drill, and they’re looking at each other, waiting for a turn, aiming if they’re throwing, and talking to me and each other. The game, furthermore, is giving me material; I’m not a lecturer, and I get most of my energy from the questions and thoughts that students bring to or make in class. In this case, their responses give me an entrée to a conversation about how 1:1 tutorials in a writing center support students at all stages of the writing process and for any writing challenge.

It’s fun with a purpose, I know. In order to teach, a teacher must build some sort of bridge — or, at least, toss a fruit loop superball — between herself and students.

It’s fun with a purpose, I know. In order to teach, a teacher must build some sort of bridge — or, at least, toss a fruit loop superball — between herself and students.

—-

Thanks to Joanne Manos and Kristen Daisy, in the Writing Center that afternoon, for their willingness to “lend a hand” to these pictures of the toys.