This weekend Eli and I will finally do some baking and thank-you-note writing for the high school teachers who wrote him the recommendation letters that helped him apply and get accepted to colleges. The baking (chocolate beet cupcakes?) is a way to recognize their labor with ours. In his notes, Eli can let them know he has decided to attend UVM out of the various schools he was accepted to.

Perhaps it’s that time of year, but I’ve been wondering about the outcome of some recommendation letters I wrote for students over the winter for internships, etc. or the personal statements I helped them revise last summer and fall for grad school applications.

On Sunday, the Social Q’s column in the New York Times published a query by a college student confused about the protocol of thanking her professor for a letter he wrote. (See photo of clipping above.) Must she thank him a second time, after learning that she got the internship? Philip Galanes, the etiquette expert, replied, “Your professor will be pleased to hear that you got the gig… [because] your success is part of his professional reward.”

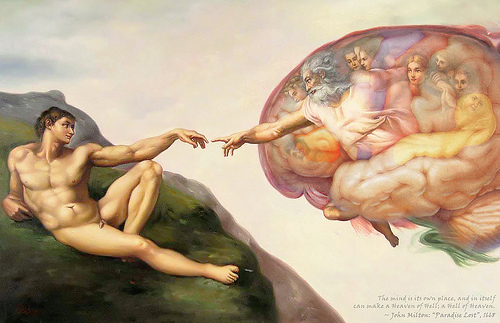

Dear Students, it’s true. We teachers are invested in your futures, just as physicians are invested in their patients’ health, and parents in their children’s well being and independence. It’s not that we are so self-effacing that we have no lives of our own — of course we have lives — but you’re like our garden. And because the processes of growth, despite all our knowledge of them, still seem so magical and the signs often imperceptible (children, like plants, seem to grow and develop overnight in the dark), it really is thrilling to see evidence that you are flourishing.

Yesterday, after a delay of almost a year, I got an email from a student who told me the outcome of his MD/PhD program applications. Together we had worked on his personal statement, he writing and I responding. He told me he has been accepted to a desirable program. Having worked with him on that personal statement, I know what this means to him.

What it means to me? I have an ego, too: In the collective work of educating young people, my individual contribution matters.