An MIT friend/colleague posted this on her Facebook page:

This week: 22 student meetings (30 minutes each), 12 student presentations to watch and grade, rehearsal for panel talk, planning meeting for IAP workshop, go to conference, give talk, come home… By next Monday I expect to be a shambling, drooling zombie.

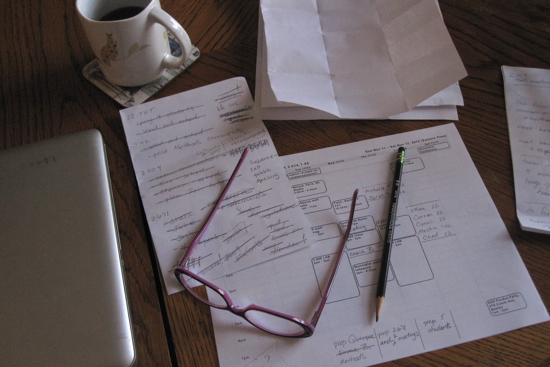

Her capsule summary of her week prompted me to print out my Google calendar and annotate it with things I needed to get done the evenings ahead of actual student meetings, deadlines, a rehearsal, a lecture. Last night I left it laid out on the dining room table. This morning it greeted me. I added the coffee.

All those cross-outs on my To Do list on the left, obviously a good thing, explains my absence from blogging. There are especially a lot of drafts to review, and in the bits of free time left over I find myself wanting to read (The Heart Broke In, by James Meek — so good), not write, or go outside instead.

Outside the windows and along the route to work, the trees are changing and getting ready to drop their garments. Watching the big Japanese maple in the backyard, which we can see outside the south-facing windows on the second floor of our house, involves the holding of one’s mental breath. The leaf color turns and turns and turns, the leaf stems continue to cling to the branches as though hanging from their fingertips, a few let go and fall, and one day soon — poof! — the rest will fall, blanketing the grass in a big crimson carpet.

This is autumn: school burdens and tensions and the lead up to the holidays, while nature relaxes. I find myself wishing for the bottom of the To Do list to be reached, quickly, and simultaneously studying the unfolding of the season.

This is autumn too: leaves to rake, fallen branches to pick up, annuals to compost, and small and noticeable steps of progress and pleasure in one’s students (and children!).

We can, at once, be getting things done and in the moment. I do not think life can be lived entirely one way or the other.

—–

The title is of course an homage to the Zombies 1968 song, “Time of the Season.” I associate this with my brother Michael, who was one of the influential disc jockeys of my childhood. This 45 got a lot of play on my parents’ record player.