Usually, we keep the cars unlocked when they’re sitting in our driveway. What would anyone want to steal, but a handful of change in the cup holder, empty water bottles on the floor, or a soccer ball in the back? An opportunistic thief, it seems, might also be attracted to a red bag full of first aid supplies for Grace’s scouting troop, of which I am the volunteer first aider. Bandaids, gauze pads, Benadryl, instant cold packs, surgical scissors, a CPR face mask: stolen. Today we replenished the kit. It costs $104 for supplies that fit this description, plus $20 for a discount backpack to hold it all.

On the MBTA Green Line, a man in nice pants, black scuffed vinyl shoes, and a puffy down Patriots jacket sat across from me, with his head bent over a notebook. Left-handed, he wrote a numbered list of principles in big block letters on the lined paper. The list, which was easy to read upside-down and across the aisle, had to do with campaigning, I gathered. “1. Door-to-door. Get the message out. 2. Phone bank. Waste of time. 3. Direct mail. Expensive, uncertain.” And so on. I feared, for some inchoate reason, he was launching the beginning of a political career.

Above ground at the Park Street Station, the street was blocked off with that yellow police tape. The whole intersection, blocked. People standing around. No cars. I looked and looked at my fellow bystanders, trying to make eye contact before asking someone to explain. No eye contact. I walked over to the hotdog stand guy. “Yes, miss?” he said to me as his glance landed on mine. I asked him what had happened. He answered, “A quite older woman was hit by a truck in the intersection. She passed away.” Oh, no. Still, I found it so strange that the gentle phrase “passed away” could be used for a victim who had been rammed by a truck.

In the rundown jewelry store on the corner of Tremont and Winter Streets, I finally got the battery in my watch replaced. Only $8.49 — what was I waiting for? For at least two months, I had been covertly using the digital display on my insulin pump as a time keeper. The jeweler’s assistant told me she sees everything out her store window, everything. The old woman who was hit by the truck had her “head cracked open. Open.” The assistant, who had heat-straightened brown hair and a very kind smile, cupped her two hands around her forehead as she described what she saw. I pictured her head like an egg, the shell opening. Continue reading

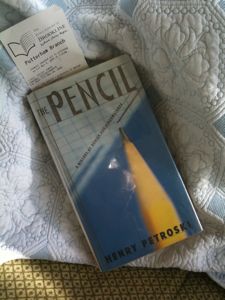

For some reason, Grace, Jimmy, and I were talking about single-noun-subject books. What concrete thing interests you enough that you would read or write an entire book about it?

For some reason, Grace, Jimmy, and I were talking about single-noun-subject books. What concrete thing interests you enough that you would read or write an entire book about it?  When it’s midterms for students, it’s midterms for teachers. (There’s something rather binge-and-purge about school, isn’t there?) In the past two weeks, since Columbus Day, I’ve been reading, commenting on, and grading the drafts of technical reports and scientific analysis papers, about 35 altogether. They’re long (average: 20 pages), but after the first few in a batch, I get into a rhythm. And while I don’t copy and paste comments from one report into another, I do notice similar issues and may make similar comments among reports.

When it’s midterms for students, it’s midterms for teachers. (There’s something rather binge-and-purge about school, isn’t there?) In the past two weeks, since Columbus Day, I’ve been reading, commenting on, and grading the drafts of technical reports and scientific analysis papers, about 35 altogether. They’re long (average: 20 pages), but after the first few in a batch, I get into a rhythm. And while I don’t copy and paste comments from one report into another, I do notice similar issues and may make similar comments among reports. Today I heard students discussing feedback that their team had received from a few instructors on a presentation. The students’ sentences uniformly began with the pronoun “they.”

Today I heard students discussing feedback that their team had received from a few instructors on a presentation. The students’ sentences uniformly began with the pronoun “they.”

“What did you find out?” That was the question I was asked when Jimmy and I returned from our one-day field trip to the Pine Barrens of New Jersey, to find

“What did you find out?” That was the question I was asked when Jimmy and I returned from our one-day field trip to the Pine Barrens of New Jersey, to find