Until I looked at Laura Splan’s watercolors in blood, I hadn’t thought of my own blood as paint or ink. Yet, it is. Many times a day I prick my finger, squeeze a drop of blood from it, and touch the drop to a test strip inserted into a glucose meter. After I’m done with the procedure, my fingertip often keeps bleeding, even though I’ve stopped being aware of it. So, as I put my hand on the mail, or a page of my glucose record log, or the Times, my blood smears and makes it mark. On paper, blood is permanent.

Before I drive or teach — two activities during which I don’t want my glucose level to drop precipitously — I check my blood sugar. Once without my noticing it I left a smudged arc across the front page of a student’s paper. As I handed it back to her in class, she noticed it, and she visibly recoiled. “Ach, what’s this?!” Oh, shit, I thought. “I’m sorry, that’s my blood. From my finger. I’m so sorry.” I knew her as a fragile person, intensely worried about her own symptoms. Damn, why couldn’t I have smudged my blood across the paper of one of the nursing students?

Clearly, the traces of my blood on paper are not intentional or artful. Still, Laura Splan’s work put me in mind of them, and I started wondering about what I could do with all those smears. At the same time, I’ve been reading this sparkling, ruminative book, I Am a Strange Loop by Douglas Hofstadter (Brian, you would like this), which has a long section on math theorums and proofs, and I’ve been thinking about how much I loved geometry and calculus in high school and college. But, I didn’t go down the math path when I could have, and that knowledge is rusty and faded.

I’m in a predicament. I can’t draw, but I want to use my blood as ink. And I can’t, really, do math, but I want to use math in some way.

Ah ha! (When I was on staff at Simmons College, I was in a cross-disciplinary workshop on teaching writing in which the participants shared a lot of cool assignments they give to students. Donna Beers, a math professor, would sometimes get her mathematics education students to write what she called a numerical autobiography. At the time, I tried writing mine, but it quickly bored me: age, weight, street addresses, telephone numbers, age of first period, age of first kiss, number of children, favorite number, et cetera. No focus, no shape.) New, better idea — I could attempt to compose a numerical memoir piece, based on my life with diabetes, and I might get Eli, one of our in-house artists, to collaborate and contribute photographs that illustrate measurable moments! (He agreed.)

I even have the draft of a beginning, which is something I cut from another piece I wrote. Its working title, which came to me as I was driving around thinking about this, refers to the many times in a day or week I have to puncture myself. I’d like it to catch the reader’s eye.

—-

Number of Pricks

For several days in the fourth week of February, 1992, I was in the hospital. I was 26 years old and eight weeks pregnant with my first child. I had learned, the morning of the day I was admitted to Brigham & Women’s, that my blood glucose was high, around 300, and that I had diabetes.

By the end of day one I started injecting myself. The nurse offered to do it, but I said, “I might as well start.” She demonstrated on an orange; I jabbed the syringe filled with insulin into the flesh at the back of my arm and plunged. Mechanically, it is not difficult.

That night, lying awake in my hospital bed, I estimated my life expectancy – I chose 76 because it was 50 years beyond my then age and 50 is an easy integer to work with — and I multiplied four injections per day by 365 days by 50 years.

Here’s the equation. Solve for X.

4 x 365 x 50 = X

My thoughts were so scattered that I couldn’t do the simple math in my head. The next day I called my father, the math teacher, who advised against calculations: Do one thing, he said, and then do the next. Don’t count beyond today, or backwards, just take the next injection. Sometimes that trite “one day at a time” advice works; what he said helped.

More than 15 years and 20,000 injections have passed since that first day. And although I have come to take the long view when it comes to diabetes and follow a regimen that I hope will get me to old age with my feet, eyes, gums, and kidneys intact, it is what I do and don’t do during any one day — the increments of insulin dosing, carbohydrate counting, blood glucose checking, aerobic exercising, and portion measuring — that adds up to a life with Type 1 diabetes.

[end of excerpt, beginning of experiment]

—–

Picture of my November 14th fingertips by Eli Guterman

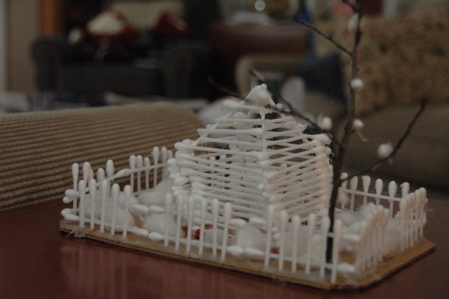

Grace channeled her cabin fever into industry today. Inspired by a spilled drum of off-brand cotton swabs, Grace started stacking them into a log-cabin-like structure, and then called for glue. I produced a lower-heat glue gun; I also handed her, unsolicited, a piece of cardboard from a discarded Amazon book box. The impulse evolved into a project, and she worked intently and inventively for a long time, even figuring out how to construct a hip roof by herself (she didn’t know she had made a hip roof until I walked back into the kitchen, saw it, and said, “Hey, a hip roof, just like on our house!”). She stripped a twig of bittersweet, in a bunch in a pitcher on the counter, of its berries and then made a tree in her little cabin’s yard. She used the red, shriveled berries as decorations around the house. I volunteered to help fashion a picket fence after she scalded herself a couple of times with hot glue.

Grace channeled her cabin fever into industry today. Inspired by a spilled drum of off-brand cotton swabs, Grace started stacking them into a log-cabin-like structure, and then called for glue. I produced a lower-heat glue gun; I also handed her, unsolicited, a piece of cardboard from a discarded Amazon book box. The impulse evolved into a project, and she worked intently and inventively for a long time, even figuring out how to construct a hip roof by herself (she didn’t know she had made a hip roof until I walked back into the kitchen, saw it, and said, “Hey, a hip roof, just like on our house!”). She stripped a twig of bittersweet, in a bunch in a pitcher on the counter, of its berries and then made a tree in her little cabin’s yard. She used the red, shriveled berries as decorations around the house. I volunteered to help fashion a picket fence after she scalded herself a couple of times with hot glue.