There is this notion of “anticipatory regret” that is supposed to make you avoid doing something bad by anticipating or imagining the negative consequences of the action. You know, you won’t lie if you imagine untangling yourself from the inevitable web of lies spun out of the first one.

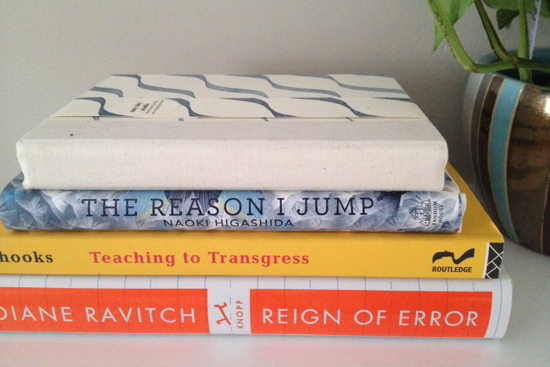

Years ago, I read the novel Therapy by David Lodge. For a long time, I attributed to that novel a different, more positive take on anticipatory regret: that it can help you do something good and desired that you imagine feeling future sadness about if you don’t do it. As I remembered the plot, I recalled that the middle-aged Tubby, who was invited to go on a pilgrimage with his former sweetheart, goes with her because he imagines that someday he could deeply regret not going.

I recently re-read Therapy — which sadly does not hold up well, though I remember it as a shining moment in my history of reading pretty much all of Lodge’s novels up to a point — and, although Kierkegaard’s arguments about regret are part of Tubby’s inner calculus, I found nothing about anticipatory regret.

Perhaps the different take was and is my own.

—–

In the spring, for one of my classes I got into the habit of holding open office hours in a classroom, so students could drop in and talk to me about the assignment and, if they wished, sit for a while and write together. One time, 10 students showed up and stayed! Another time, only one did, but he stayed for two hours to work on his report. He would write, ask me a question, write again, say something out loud, write again, and so on. “What do you write?” he asked me at one point. This was an unexpected question, it being a computer science (writing) class and me so clearly not a computer scientist. Why would he, or any CS student, care?

I hemmed. I hawed. “I have written some essays… tried my hand at poetry… last summer wrote a story.”

“What about a book?”

“Well, a while ago I started working on a novel, but then I stopped because I thought it might not be so good for my mental health.”

“What do you mean?” He was still looking at his own screen, writing.

“Like, the story was too close to home. I wondered if I should be getting my thinking in order instead of projecting it all on a novel.” As I was saying this, it sounded stupid to my own ears.

“THAT IS MESSED UP!” he exclaimed, kind of laughing. “That does not make any sense.”

I, sheepishly, “Well, it did to me, at the time. But, yeah.”

—–

You know, when you say something out loud, or you write it down, then you have to think about it.

—–